There is a lot of speculation about which the path the Israelites traveled when they left Egypt–which is strange, because the statements of the Bible are clear. This article interacts with the Biblical text and a modern study Bible to lay out the Bible’s teaching.

Originally published as Från träldom till det utlovade landet in Biblicum Volume 84 Number 3, 2020. Biblicum, Hantverkaregatan 8 B, SE-341 Ljungby, www.biblicum.se . Translated to English by Julius Buelow.

Exodus: From Slavery to the Promised Land

Seth Erlandsson

The Bible repeatedly cites the deliverance from slavery in Egypt as the great picture of the work of salvation which God’s One and Only Son, the Messiah, would accomplish once for all when the time had come. “But when the set time had fully come, God sent his Son” (Gal 4:4, EHV) to save us from the slavery of sin. This deliverance is entirely a work of God, a miracle, something that humanly speaking is completely impossible because of humanity’s sinful corruption.

The slavery which Jacob’s offspring, the Israelites, suffered in Egypt was predicted by God long before. Speaking to Jacob’s grandfather Abraham, God said, “Know this! Your descendants will live as aliens in a land that is not theirs, and they will serve its people, who will afflict them for four hundred years” (Genesis 15:13, EHV). Because of a severe famine in Canaan, Jacob and his sons came to Egypt and settled there (ca 1876 BC) with the help of his son Joseph, who rescued them. Joseph already lived in Egypt because he had been sold as a slave by his brothers, though later he was exalted and became Pharaoh’s right hand man.

When “a new king arose in Egypt, who did not know Joseph” and Jacob’s offspring became numerous in the land, they were oppressed with forced labor. “The Egyptians oppressed the Israelites by forcing them to work very hard” (Ex 1:8, 11, 13, EHV). But despite “all kinds of work” with which the Egyptians oppressed them (1:14, EHV), the Israelites continued to increase in number, so much so that they were seen as a threat to the security of the kingdom. Then Pharaoh gave the following command: “Every son who is born you shall throw into the Nile” (1:22, EHV).

Moses and his mission of liberation

When Moses was born ca 1526 BC, around 350 years after his people arrived in Egypt, he was also to be thrown into the Nile. But his mother hid him for three months and afterwards put him in a basket which she placed in the reeds on the banks of the Nile. This became Moses’ deliverance, because Pharaoh’s daughter saw the child when she came to bathe and “felt sorry for him” (Ex 2:6, EHV). She decided to adopt Moses as her son. But when he was forty years old (Acts 7:23) and saw the difficult slave labor of his Hebrew brothers, and how an Egyptian beat a Hebrew man, he couldn’t restrain himself: “After he looked this way and that, and he saw that no one was there, he struck down the Egyptian and hid him in the sand” (Ex 2:12, EHV). But the truth came out, and Pharaoh wanted to punish Moses with death. So he fled to the land of Midian, which lies east of the Gulf of Aqaba in northwest Saudi Arabia.

In Midian, Moses married Zipporah, one of the daughters of Jethro the priest. There he lived for forty years, working for his step-father as a shepherd. “When forty years had passed” (Acts 7:30) he was given the difficult mission of returning to Egypt in order to lead the Israelites out of Egypt to the Promised Land. “The Angel of the LORD,” that is, the eternal Son of God sent to sinners, the Mal’ak = “The One Sent Out” by the Father (cp. John 5:23; 7:33; 8:42; 12:44,45), “I Am” (Ex 3:13f; John 8:58; 10:30), revealed himself to him and commissioned him. Moses describes how it happened (speaking of himself in the 3rd person): “He led the flock to the far side of the wilderness and came to Horeb, the mountain of God. The Angel of the LORD appeared to him in blazing fire” (Ex 3:1-2, EHV). He said, “I am the God of your fathers, the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob.” Moses hid his face, because he was afraid to look at God. The LORD said, “I have certainly seen the misery of my people in Egypt, and I have heard their cry for help because of their slave drivers. Yes, I am aware of their suffering. So I have come down to deliver them from the hand of the Egyptians and to bring them up out of that land to a good and spacious land, to a land flowing with milk and honey” (Ex 3:6-8, EHV).

Moses’ assignment read: “I will send you to Pharaoh to bring my people, the Israelites, out of Egypt” (3:10, EHV). What an impossible assignment for someone who earlier in his life had to flee from Egypt after committing murder! It’s no wonder that Moses tries to talk his way out of it. “Who am I, that I should go to Pharaoh and that I should bring the Israelites out of Egypt?” (3:11, EHV). Then Moses receives this promise: “I will certainly be with you…” (3:12, EHV). “But I know that the king of Egypt will not allow you to go unless he is forced to do so by a powerful hand. So I will reach out my hand and strike Egypt with all my wonders which I will do in their midst. Afterward he will let you go” (3:19-20, EHV). It is God who guarantees that this mission will be a success. Even so, Moses doubts and comes up with a slew of excuses to try to get out of this difficult assignment (see 4:1ff).

From Midian back to Egypt

When Moses made it back to Jethro’s home after the revelation at God’s mountain, Horeb, the LORD revealed himself to Moses once again: “Go, return to Egypt, for everyone who wanted to kill you is dead” (4:19, EHV). After these words from the Lord (“everyone who wanted to kill you is dead”), the last vestiges of Moses’ doubt were removed, and his stepfather agreed with Moses’ plan to return to Egypt together with his family. “So Moses took his wife and his sons, placed them on a donkey, and set out to return to the land of Egypt” (4:20, EHV). He had the staff of God with him, because the Lord had said to him: “When you go back to Egypt, make sure that you perform in the presence of Pharaoh all the wonders which I have put into your hand. However, I will make his heart hard, and he will not let the people go” (4:21, EHV).

Moses was eighty years old and his brother Aaron was eighty-three (7:7) when they came back to Egypt and came before Pharaoh and presented the demand that the Israelites be set free. Just as the LORD had said he would, Pharaoh refused to let the people go despite clear evidence of the LORD’s power and the powerlessness of the Egyptian gods. Only after the 10th plague, the death sentence carried out against every firstborn, did Pharaoh no longer refuse to release the people—both young and old, sons and daughters, and even sheep and cattle (10:9). The judgment struck all the firstborn in the land of Egypt, “from the firstborn of Pharaoh, who sits on his throne, to the firstborn of the female slave who is behind the hand mill, even all the firstborn of the livestock” (11:5, EHV).

A Hasty Flight from Egypt

According to the Lord’s words to Moses and Aaron, the children of Israel were to be ready for a hasty flight as soon as they had eaten the Passover lamb, whose blood delivered the Israelites: “This is how you are to eat it: with your cloak tucked into your belt ready for travel, your sandals on your feet, and your staff in your hand. Eat it in haste” (12:11, EHV). The Lord “passed over” (hebr. פָּסַח) the homes of the children of Israel in Egypt when, at midnight, he struck all the firstborn in the land of Egypt. “During the night Pharaoh got up—he, all his servants, and all the Egyptians—and there was a loud outcry in Egypt, for there was not a house where there was not someone dead. Pharaoh summoned Moses and Aaron that night and said, “Get up, get away from my people! Both you and the Israelites, go, serve the Lord, as you have said! Take also your flocks and your herds, as you have said, and go! But also bless me!” The Egyptians urged the people to leave the land quickly, for the Egyptians said, “We are all going to die! The Israelites took their dough before it was leavened…” (12:30-34, EHV).

“It was a night that the LORD kept vigil to bring them out of the land of Egypt” (12:42), “about six hundred thousand men on foot, besides their families” (12:37, EHV). They marched with haste, day and night: “The Lord went in front of them in a pillar of cloud by day to lead them on their way and in a pillar of fire by night to give them light. In this way they could travel by day and by night. The pillar of cloud by day and the pillar of fire by night never left its place in front of the people” (13:21-22, EHV). They needed to flee the land of slavery as quickly as possible. “On the day after the Passover (hebr. פָּסַח), the people of Israel went out triumphantly in the sight of all the Egyptians, while the Egyptians were burying all their firstborn, whom the Lord had struck down among them. On their gods also the Lord executed judgments” (Nu 33:3-4, ESV).

The entire march from Egypt was a miracle throughout—not just the deliverance from the 10th plague through the blood of the lamb, but also how God, in a pillar of cloud and fire, led them out of Egypt by day and night, and cared for them during their wandering: “I carried you on eagles’ wings” (Ex 19:4, EHV). “I led you through the wilderness for forty years. Your clothing did not wear out on you, nor did the sandals on your feet” (Dt 29:5, EHV).

Which road did the Israelites take on their way from Egypt to the Promised Land?

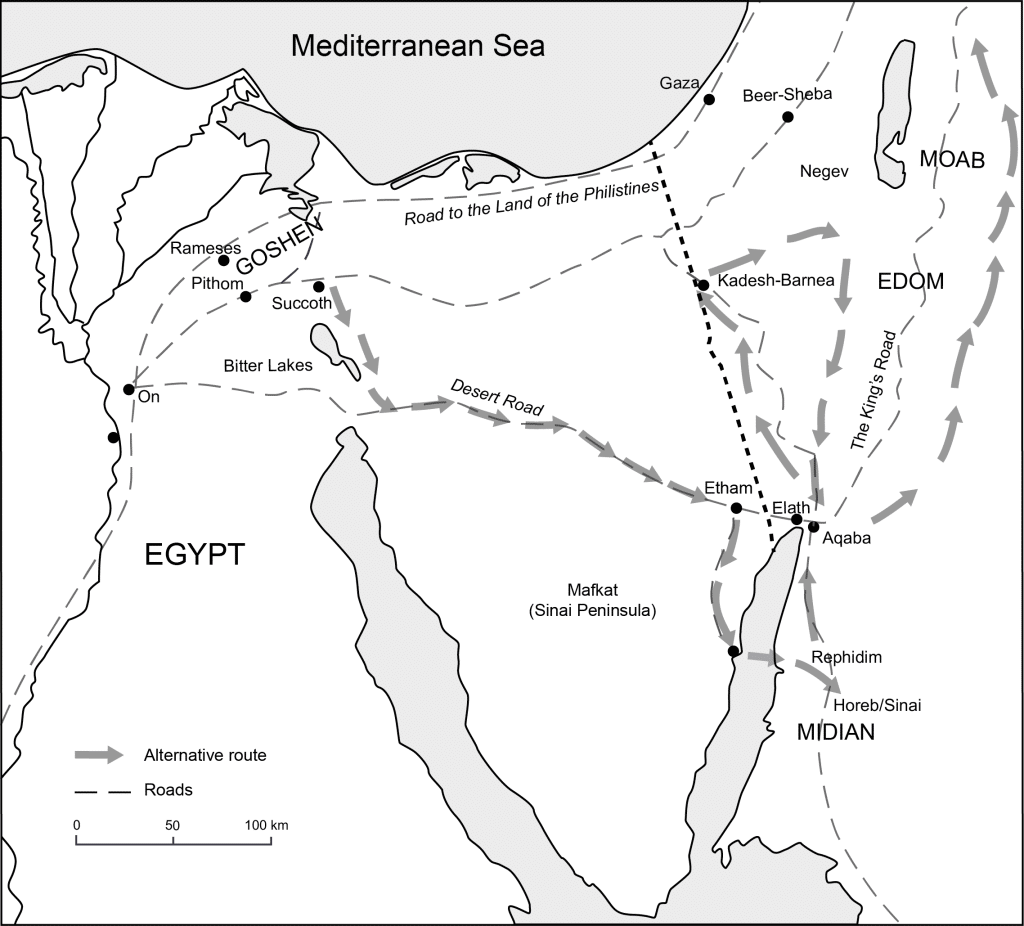

There’s a lot of speculation about which road the Israelites took to leave Egypt—which is strange, because the statements of the Bible are clear. Moses’ assignment from God was to lead the children of Israel out of Egypt to the land of Canaan, not way down to the Southern part of the Sinai Peninsula which was under Egyptian control. The LORD had said to Moses: “I will bring you up from the misery in Egypt to the land of the Canaanites, the Hittites, the Amorites, the Perizzites, the Hivites, and the Jebusites, to a land flowing with milk and honey” (Ex 3:17, EHV). There were several roads that went there: “The road to the land of the Philistines” (דֶּ֚רֶךְ אֶ֣רֶץ פְּלִשְׁתִּ֔ים), which was “nearby” (13:17, CSB), a middle road, and the great trade road—the “wilderness road to Yam-suf” (דֶּ֥רֶךְ הַמִּדְבָּ֖ר יַם־ס֑וּף) (13:18, SE) that would then lead directly north from present day Eilat. God, who was leading the exodus in a pillar of cloud and fire (The Mal’ak, The Son Sent Out By God, cf. 14:19) did not choose the “road to the land of the Philistines”. Why? This decision needed explanation: “If the people face war, they may change their minds and return to Egypt” (13:17). “So God led the people on a detour via the wilderness road to Yam-Suf” (13:18, SE).

“The wilderness road to Yam-Suf” was well known to both Moses and Aaron. It was this road that Moses took when he fled to the land of Midian, and it was this road he, together with Aaron, had recently taken in the other direction when they traveled around the Gulf of Aqaba on their way from Midian to Egypt. Which sea is meant, then, by Yam-Suf? A number of Bible passages present the clear answer. The sea referred to is the Red Sea’s Gulf of Aqaba. Cf. Ex 23:31; Nu 14:25; 21:4, Dt 1:40, 2:1; 1 Kings 9:26 and Jeremiah 49:21! In all of these passages the Red Sea’s Gulf of Aqaba is meant. The early translations, the Septuagint and the Vulgate, render Yam-Suf as “the Red Sea” (Greek: ἡ ἐρυθρὰ θάλασσα and Latin: mare rubrum). Many other later translations do the same (in Sweden, among others, Kyrkobibeln 1917 and SFB 2015).

But what does Yam-Suf really mean?

Yam (יַם)means “sea”[2] and suf (סוּף) means “reach its end, cease, be destroyed.”[3] A literal translation should then be “The sea of the end” or “the sea of destruction.” In the Old Testament, places often receive a name that will bring to mind what happened there. Several examples:

- After the Israelites made the long crossing directly through Yam-Suf, they came to a place where they finally found water, yet couldn’t drink it because it was bitter. That place was named Mara, which means “bitter” (Ex 15:23). The name of this place would cause people to remember that the Lord performed a miracle there by making the water sweet.

- Jacob gave the place where he wrestled with God the name Peniel which means “God’s face”, because he thought: “I have seen God face-to-face, and my life has been spared” (Gn 32:30, EHV).

- In a dream Jacob saw a ladder going up to heaven, and saw God at the top of the steps. He called that place Bethel which means “God’s house.” When he woke up, he said: “Certainly the LORD is in this place… This is nothing other than the house of God, and this is the gate of heaven” (Gn 28:16,17, EHV).

In the same way, Moses surely used the name Yam-suf to remind people that in this sea, the pursuers and oppressors of God’s people met their destruction, their end. Yam-Suf, “the sea of destruction” is therefore an appropriate name for the Red Sea’s Gulf of Aqaba, because in this sea the pursuing Egyptians were destroyed through the miraculous intervention of God.

Suf can also mean “reed”[4] and for this reason many have translated Yam-Suf as “Sea of Reeds.” But that translation says nothing about the miracle, that in that place God defeated the pursuing enemies. That translation also does not harmonize with the Biblical tendency to use a name to remind people of what happened there, in this case, God’s incomprehensible miracle of salvation that was to be praised. Note how Exodus 15, immediately after the great miracle of salvation, praises the LORD for how he intervened and defeated the Egyptians when the children of Israel were hopelessly trapped before the Red Sea’s Gulf of Aqaba:

“He has cast Pharaoh’s chariots and his army into the sea.

His elite officers are drowned in the Red Sea (Yam-Suf).

The deep waters covered them.

They sank down to the depths like a stone” (15:4,5, EHV).

“At the blast from your nostrils the waters piled up.

The flowing waters stood up like a dam” (15:8, EHV).

“But you blew with your breath, and the sea covered them.

They sank like lead in the mighty waters” (15:10, EHV).

The Psalmist also praises the LORD for the miracle of salvation at Yam-Suf:

“So he saved them from the hand of the foe and redeemed them from the power of the enemy.

And the waters covered their adversaries; not one of them was left.

Then they believed his words; they sang his praise. But they soon forgot his works” (Psalm 106:10-13, ESV).

Where and why were the Israelites trapped?

“The wilderness road to Yam-Suf” went (and has always gone) in the direction of the northern point of the Gulf of Aqaba. By following that road the people could leave the Sinai Peninsula, which was under Egyptian control. The Sinai Peninsula was originally called Mafkat, the land of turquoise. From early on the Egyptians had mines in the southern region of Mafkat, where turquoise was very prevalent. The mines are considered some of the world’s most ancient mines that have been discovered. It is likely that even Israelites were used as slaves in these mines. This is suggested by the fact that several early proto-Sinaitic inscriptions, from between 1840-1450 BC, contain the earliest traces of the Hebrew alphabet (see Douglas Petrovich, The World’s Oldest Alphabet: Hebrew As the Language of the Proto-Consonantal Script, Carta Jerusalem 2016; and Biblicum no 2/2017, p 64ff). If the Israelites were still on the Mafkat peninsula, the risk would be great that the Egyptians would make them slaves again.

When the Israelites left Ramses and Sukkoth, they marched day and night in “groups of 50” (13:18, SE, וַחֲמֻשִׁ֛ים), and didn’t set up camp until they were “at Etham, at the edge of the wilderness” (13:20; Nu 33:6, EHV). We don’t know for sure what is meant by Etham and where it was. But it probably refers to the towering mountain ranges (with peaks more than 2,500 meters high) which the sandy and relatively flat wilderness road arrives at when there is about a quarter of the journey remaining on the wilderness road to the northern point of the Gulf of Aqaba. This mountainous landscape surrounds the northern part of the Gulf of Aqaba and slopes sharply down towards the Gulf of Aqaba, like a wall on both sides. Etham is used to refer to both sides of the northern part of the Gulf of Aqaba—in Exodus 13:20 of the west side and in Numbers 33:8 of the east side. The east side is called both “Etham’s wilderness” (Nu 33:8) and “the wilderness of Shur” (Ex 15:22). Maybe the word Etham meant “red” (like Edom) because the slopes of the mountain have a red sheen. Shur means “wall,” [5] so the name “the wilderness of Shur” fits well with the northern part of the Gulf of Aqaba, since, from a distance, the mountains around this sea look like a wall.[6]

When, after several days of marching, the children of Israel were close to freedom beyond Pharaoh’s control,[7] something strange happened. The LORD said to Moses: “Tell the Israelites to turn and camp in front of Pi Hahiroth, between Migdol and the sea. They are to camp by the sea, facing Baal Zephon. Then Pharaoh will say about the Israelites, ‘They have gone astray in the land. The wilderness has shut them in’” (Ex 14:2-3, SE). Hir (like חוּר) means “bore, dig a hole,” [8] and the only road that turns toward the sea is a road that digs its way like a winding ravine through the mountainous landscape down toward the Gulf of Aqaba. This “ravine road,” which today is called Wadi Watir (The Wadi Ravine), opens out into a broad and even cape with plenty of room for the multitudes of Israelites to set up camp, recover and rest (though the rest proves to be short-lived). Pi (פִּי) means “mouth, opening,” so Pi-Hachirot means “the mouth of the ravine road.” This can be seen clearly on any map, and today is called Nuweiba (Migdol means “watch tower”). Baal Sefon was “across from” (Hebr. נִכְחוֹ) Pi-Hachirot (the opening of the ravine road), and was probably a known religious site for idol worship directly across on the other side of the Gulf of Aqaba.

Why did the Lord command the children of Israel to turn off the wilderness road and take the ravine road, which was a winding ravine and a dead end down to Pi-Hachirot? The answer is given in Ex 14:3ff: The Lord wanted Pharaoh to believe that the Israelites had gotten lost and become trapped in the wilderness (v. 3). “I will harden Pharaoh’s heart so that he will pursue them, and I will gain glory through Pharaoh and his entire army” (v. 4, EHV). And that is what happened. When Pharaoh received reports that the Israelites had taken the ravine road to the sea, he regretted that he had released the Israelites, his source of much-needed slave labor. So he now sent out his army with its leading warriors in order to capture the fugitives (v. 5-7). After all, they had only requested and received permission to “go on a three-day journey into the wilderness so that we may sacrifice to the LORD” (Ex 3:18, EHV; see also 5:3; 8:27).

Moses must have had a hard time understanding why the Lord, through the pillar of cloud and fire, was now leading them down a blind alley directly to the sea. Indeed, he knew the wilderness road well, and knew that taking it would deliver them from Egyptian control. But as a witness to the great miracles the LORD had carried out during the course of the ten plagues, he had learned that he could trust the Lord. The people, on the other hand, did not have the same trust in the LORD. They became terrified when they reached the mouth of the ravine road and set up camp because they understood that they were trapped. When Pharaoh’s army drew near the Israelites were terrified and cried out to the LORD. And they said to Moses: Is it because there are no graves in Egypt that you have taken us away to die in the wilderness? What have you done to us in bringing us out of Egypt? Is not this what we said to you in Egypt: “Leave us alone that we may serve the Egyptians”? For it would have been better for us to serve the Egyptians than to die in the wilderness (14:11-12, ESV). The Psalmist writes: “Our fathers in Egypt did not learn from your miracles; they did not consider your many acts of mercy, but instead rebelled at the sea, at Yam-Suf” (Psalm 106:7, SE).

The Israelites seemed hopelessly doomed, that is, unless the Lord would save them through a miracle—and the people did not believe that was going to happen. But Moses did. He said to the people: “Don’t be afraid. Stand firm and see the LORD’s salvation that he will accomplish for you today; for the Egyptians you see today, you will never see again. The LORD will fight for you, and you must be quiet” (Ex 14:13-14, EHV). But even Moses couldn’t stay entirely calm under the fearsome circumstances. He couldn’t “be quiet,” instead he cried out to the Lord for help, which he himself admits when by recording the Lord’s response: “Why are you crying out to me? Tell the Israelites to set out” (v. 15, EHV).

But how could they “set out” when they had a large sea in front of them blocking their way? “Lift up your staff, stretch out your hand over the sea, and divide the sea so that the Israelites can go through the middle of the sea on dry ground” (v. 16, EHV). But what about the pursuing Egyptians that are about to overtake us? “I will gain glory through Pharaoh and his entire army, through his chariots and his charioteers” (v. 17, EHV). “Then the Angel of God, who was going in front of the Israelite forces, moved and went behind them. The pillar of cloud moved from in front of them and stood behind them. It went between the Egyptian forces and the Israelite forces. The cloud was dark on one side, but it lit up the night on the other. Neither group approached the other all night long” (v. 19-20, EHV).

Moses believed God’s promise and did as the LORD said: “Moses stretched out his hand over the sea” (v. 21a, EHV). And, as always, God kept his promise: “all night long the LORD drove the sea back with a strong east wind and turned the sea into dry land. The waters were divided. The Israelites went into the middle of the sea on dry ground. The waters were like a wall for them on their right and on their left” (v. 21b-22, EHV).

But even though the Egyptians were prevented from reaching the Israelites, they pursued them into the heart of the sea:

The Egyptians pursued them, and all of Pharaoh’s horses, his chariots, and his charioteers went after them into the middle of the sea. During the last watch of the night, the LORD looked down on the Egyptian forces from the pillar of fire and cloud. Then he confused the Egyptian forces. He jammed their chariot wheels, and they had difficulty driving them. The Egyptians said, “We must flee from Israel, for the LORD is fighting for them against Egypt!” Then the LORD said to Moses, “Stretch out your hand over the sea, and the waters will come back over the Egyptians, over their chariots and their charioteers.” So Moses stretched out his hand over the sea, and at daybreak the sea returned to its normal place (v. 23-27a, EHV).

Now it was the Egyptians who had to flee: “While the Egyptians were fleeing from it, the LORD threw the Egyptians into the middle of the sea. The waters came back and covered the chariots and the charioteers, the entire army of Pharaoh that went into the sea after the Israelites. Not even one of them survived” (v. 27b-28, EHV). What an incredibly great miracle this is! The impossible happened: “But the Israelites went through the middle of the sea on dry land, and the waters were like a wall for them on their right and on their left. On that day the LORD saved Israel from the hand of the Egyptians, and Israel saw the Egyptians dead on the seashore” (v. 29-30). This miracle is so incredibly great and powerful that it is able to foreshadow the salvation to come through Jesus Christ. It has power to create both faith and the song of praise that comes from that created faith (14:31b-15:18). That song of praise concludes by repeating the amazing miracle: the enemies were destroyed and “the Israelites walked on dry land in the middle of the sea” (15:19, EHV).

Why is the destination Horeb, the mountain of God?

God hadn’t forgotten the promise he had given to Moses at “Horeb, the mountain of God,” when he called him and commissioned him to deliver the Israelites (Ex 3:1ff). He said, “I will certainly be with you. This will be the sign to you that I have sent you: When you have brought the people out of Egypt, you will serve God on this mountain” (3:12, EHV). Now they had left Egypt and Mafkat (the Sinai Peninsula) and even taken a shortcut to the mountain where the LORD had appeared to Moses during the time he had been tending his stepfather’s sheep in the land of Midian.

Where, then, was “Horeb, the mountain of God” located? Many have guessed that it was way down in the Southern portion of the Sinai Peninsula. But in that case, the land of Midian must have been there as well. That is not the case. The text of the Bible gives clear proof of that. The land of Midian was in the east, east of the Gulf of Aqaba, in what is now the northwestern part of Saudi Arabia. Genesis 25:6 talks about the sons Abraham had with his concubine Keturah, Medan and Midian—among others. It says that Abraham sent them east to the land of the east.

As we have already seen, “The Sea of Destruction” (Yam-Suf) refers to the Gulf of Aqaba, that is, the sea where the Egyptians met their destruction. After the miraculous parting of the sea, Moses reached the mountain where he had received his calling. When he had set up camp at the mountain of God, his stepfather came to meet him there (Ex 18:5-6). So the mountain of God, Sinai, could not have been located on what is now known as the Sinai Peninsula. Jethro took with him “Moses’ wife Zipporah, whom Moses had sent home earlier. He also had with him her two sons. One of them had been named Gershom, for Moses had said: ‘I am a foreigner (hebr. גֵּר) in a foreign land.’ The other had been named Eliezer, for Moses said: ‘The God of my fathers came to my help (hebr. עֵ֫זֶר) and saved me from the sword of Pharaoh’” (Ex 18:2-4). Moses was supposed to have been executed if he had stayed in Egypt. Now, forty years later, Moses had much to tell about the mighty deeds of the LORD and what the Israelites had all just experienced: “Moses told his father-in-law about everything that the LORD had done to Pharaoh and the Egyptians for Israel’s sake, about all the hardships that had confronted them along the way, and how the LORD had delivered them. Jethro rejoiced over all the good things that the LORD had done for Israel when he delivered them from the hand of the Egyptians” (18:8,9).

Still today there is a large settlement called Al Bad in the land of Midian. In that place there is permanent access to water, a prerequisite for any large settlement in the wilderness. After Moses had fled to Midian, he came to a large settlement in the wilderness, for Jethro was the priest there, and thereby also the leader. It is written that Moses sat by a well and that Jethro’s seven daughters came there to draw water for their sheep (Ex 2:15-17). It is also written that forty years later, when Moses was tending his stepfather’s sheep, he came to the “other side of the wilderness” (3:1-2), for there is a mountain range north of Al Bad which borders the wilderness of Sin. This mountain range is apparently Horeb, because on the other side of this range, toward the east, is its highest peak. Beneath this peak the Angel of the LORD appeared to Moses in a flame (3:1-2). He had come to “Horeb, the mountain of God,” or, as it is also called, “Sinai,” because it was located in the wilderness of Sin (cf. 16:1). Today this peak bears the Arabian name Jabal el-Lawz.

Beneath this mountain is a large plateau with plenty of room for over two million Israelites to set up their tents and live there for almost a whole year. They arrived there “in the third month after the Israelites had left the land of Egypt” (Ex 19:1, EHV), that is, one and half months after the exodus, and they set out from there “on the twentieth day of the second month, in the second year” (Nu 10:11, EHV). But isn’t Mount Sinai on the Sinai Peninsula? That is what Helena, the mother of Emperor Constantine the Great, believed. But beneath this mountain there is no room for over two million Israelites to set up camp, and this mountain also is not located on the other side of the Gulf of Aqaba where Jethro lived.

During her long pilgrimage from 326-328 AD, Helena not only thought that she had found the true cross of Christ in Jerusalem, but she also believed that in the southern portion of the Sinai Peninsula she had found the mountain where Moses received the two stone tablets. I have not been able to find evidence that Mafkat was called the Sinai Peninsula already before Helena claimed she had found Mount Sinai there. Even so, it cannot be ruled out that there were several mountains called Sinai. But according to the book of Exodus, Horeb, the Mountain of God, was located east of the Gulf of Aqaba. The Apostle Paul himself knew that the Sinai where God revealed himself to Moses was in Arabia. For when he wrote to the Galatians about the two covenants, he said: “One is from Mount Sinai, bearing children into slavery. This is Hagar. You see, this Hagar is Mount Sinai in Arabia, and she corresponds to present-day Jerusalem, because Jerusalem is in slavery along with her children” (Gal 4:24, 25, EHV).

A strong tradition that stems from the queen mother’s claims about Sinai

For a long time most Bible interpreters have started with the assumption that Helena’s placing of Sinai (where the myth-enshrouded St. Catherine’s Monastery was built) is correct, without carefully studying whether this identification reconciles with the testimony of the Bible about the exodus from Egypt. One of the consequences of this is that Yam-Suf—in direct contradiction to a plethora of Bible verses (see above)—is said to refer to some sea immediately east of the Nile delta, about where the Suez Canal is today. Among other places, people have suggested an inlet of the Mediterranean, the Sea of Timsah, one of the Bitter lakes, or that the Gulf of Suez used to reach further north. “The wilderness road to Yam-Suf” is not permitted to be the wilderness road to the northern point of the Gulf of Aqaba, that is, the name of the first part of the ancient caravan route “The King’s Road” which then continues north to Syria and beyond Syria (i.e. Assyria, see footnote 5 above). Instead, Yam-Suf is interpreted as a southern road in the direction of the lower part of the Sinai Peninsula. This interpretation has become such a strong tradition that it is permitted to force an interpretation of Exodus that, in my opinion, comes into conflict with the Bible at several points.[9]

I appreciate the valuable new Bible translation Evangelical Heritage Version (EHV) very much, as well as its Study Bible (Notes) which can be downloaded from Logos for Logos Bible Software. But when it comes to the exodus from Egypt these Notes are unfortunately also steeped in the strong tradition I’ve described above. Here are several examples:

- “The major obstacle on the direct coastal road was not the Philistines, but the heavily fortified Egyptian frontier. This frontier was also protected by a 200-foot-wide barrier canal, which may have run from the Mediteranean Sea to Pi Hahiroth.”

Response: The text of the Bible says nothing about a heavily fortified border which would supposedly be “the major obstacle on the direct coastal road.” The reason for avoiding this road was: “If the people face war, they may change their minds and return to Egypt” (Ex 13:17, EHV). Nor does the Bible mention any impassible geographical obstacle that would prevent people from leaving or entering Egypt proper. Abraham and Sarah had no problems visiting Egypt (Gn 12:10ff), nor Jacob and his sons (Gn 42-46). Moses was not prevented by some type of barrier when he fled from Egypt and took the wilderness road to the land of Midian to the other side of the Gulf of Aqaba. Both Moses and Aaron were able to take the wilderness road, both to Midian and back again to Egypt. Moses was able to send his family ahead of him back to Jethro and the land of Midian (Ex 18:2). The people did not take a detour because they were stopped by a water barrier or by border guards; they were led by God to turn down to “the wilderness road to Yam-Suf” (Ex 13:18). Pharaoh had given the Israelites permission to emigrate: “Get up, get away from my people! Both you and the Israelites, go, serve the LORD, as you have said!” (Ex 12:31, EHV). The border crossing out of Egypt proper would therefore not have been a problem. The Egyptians even “urged the people to leave the land quickly, for the Egyptians said, ‘We are all going to die!’”(v. 33, EHV).

- “The Exodus account also makes it clear that the crossing site was on the border of Egypt, not after Israel had already crossed the Sinai Wilderness.”

Response: But is this really true? The text clearly says: because the LORD went ahead of them in a pillar of cloud and fire, nothing was stopping them from leaving Egypt quickly and from traveling “by day and by night” on the wilderness road to Yam-Suf (13:21). Several Bible passages show (see above) that Yam-Suf refers to the Gulf of Aqaba. Only when the Israelites are close to reaching the peak of the Gulf of Aqaba, and only when they are very close to completely leaving Egyptian territory, are they given the faith-testing order to turn down toward the sea (14:2), which would leave them trapped before the Gulf of Aqaba. The reason for this strange order is given in the text: Pharaoh would think, “They have gone astray in the land. The wilderness has shut them in” (14:3). The only way which turns off the wilderness road and leaves one trapped before the Gulf of Aqaba is the ravine road Hachirot whose mouth (Pi) is a wide cape where there is plenty of room to “camp by the sea” (14:2, EHV).

The time references in Exodus also show that the crossing over the sea did not happen already at the start of the exodus. When they had come to the other side of the sea and reached Elim, almost a whole month had passed (see Ex 16:1). So the crossing over the sea must have happened at least 20 days after the start of the exodus. In addition, the crossing of the sea was an event of such magnitude that it could not correspond to any crossing that happened in a place immediately after the start of the exodus (see Exodus 15 and Psalm 106:10-13).

- “The location of Mount Sinai is not certain, but there is strong tradition for the site that now is the location of St. Catherine’s Monastery.”

Response: Yes, there is a strong tradition, but the support from the text is weak. Moses was in the land of Midian on the other side of the Gulf of Aqaba when he came to Horeb and Sinai and received his call. It is to this mountain that the departing Israelites come, just as God promised. The mountain was located in the land of Midian, for Moses’ family, whom he had sent home earlier, rejoin him there, together with Jethro. The map about the path of the Exodus included in the Study Bible Notes rightly place Midian on the east side of the Gulf of Aqaba, but place Sinai very far away from there on the west side, where St. Catherine’s Monastery is located. How can that be reconciled?

- “Exodus 15:22 states that after crossing the Red Sea, the Israelites found themselves in the wilderness of Shur. The wilderness of Shur is east of the Gulf of Suez and in the western area of the Sinai (Genesis 16:7; 1 Samuel 15:7). To cross the Red Sea and to end up in the wilderness of Shur, Israel could be crossing only the westernmost arm of the Red Sea and not the Gulf of Aqaba.”

Response: If it is true that “the wilderness of Shur” is “east of the Gulf of Suez and in the western area of the Sinai,” then the Bible seems to contain contradictions. Many Bible verses clearly show that Yam-Suf is the same as the Gulf of Aqaba and that Sinai was located in Midian, east of the Gulf of Aqaba.

Commenting on Genesis 16:7 and 1 Samuel 15:7 requires a little exposition on the texts where Shur comes up. These texts deal with people and tribes who lived east of Israel and in Arabia and are called “people of the East” (in Hebr. בְנֵי־קֶדֶם). People of the East were, like Edom and Moab, hostile to Israel. They wanted to prevent God’s act of salvation, the rescue from slavery in Egypt. Among those Easterners who opposed Israel were the Amalekites at Rephidim, near Horeb (see Ex 17:8ff), as well as Edom and Moab when the Israelites, after a long 40-years of wandering in the wilderness, wanted to travel through their lands. The territory of Edom lay directly south of the Dead Sea down to the northern point of the Gulf of Aqaba with its western border against Israel. The territory of Moab lay east of the southern part of the Dead Sea.

Ishmaelites, Midianites, and Amalekites were designated as “Easterners/People of the East.” They were nomads or partial nomads. Ishmael was the son of Abraham’s concubine Hagar. The Angel of the LORD said to Hagar: “He will live east of (literally: “before the face of”) all his brothers” (Gn 16:12 SE; The EHV translates: “He will dwell in hostility toward all his brothers.”). Genesis 25:18 says about the descendants of Ishmael: They “lived from Havilah up to Shur, east of Egypt, where the road goes toward Assyria” (SE). Havilah means “land of sand” and stands for the Arabian wilderness which was “east of Egypt”. The road which goes toward Assyria” was called “the King’s Road” and was a known caravan road which went from Egypt and, at the northern point of the Gulf of Aqaba, turned directly north, running east of the Dead Sea and the Jordan River. Shur, which means “wall” (see above), obviously refers to the northern region around the Gulf of Aqaba. According to Exodus 23:31, the border of Egypt ran from “the Gulf of Aqaba (Yam-Suf) to the Sea of the Philistines” (מִיַּם־סוּף֙ וְעַד־יָ֣ם פְּלִשְׁתִּ֔ים). So “east of Egypt” probably also means east of the Egyptian-controlled Mafkat (later called the Sinai Peninsula). Genesis 16:7 states that the Angel of the LORD met the fleeing Hagar “on the road to Shur” (EHV translates “on the way to Shur”), that is, probably heading in the direction of the northern point of the Gulf of Aqaba.

Midian was the son of Abraham’s concubine Keturah (Gn 25:2). “The sons of his concubines… he sent them away from Isaac his son to the territory that lay to the east” (Gn 25:6, EHV), in hebr.: קֵ֖דְמָה אֶל־אֶ֥רֶץ קֶֽדֶם, “eastward to the land of the east.” The Kenites were a tribe of Midian that was not hostile to Israel. Moses’ stepfather Jethro (Reguel) belonged to this tribe.

Amalek was the grandson of Esau (Edom). According to 1 Samuel 15, the LORD said to Saul: “I will repay Amalek for what they did to Israel when they blocked Israel’s way as it was coming up out of Egypt. Go and strike Amalek. Devote everything they have to destruction” (v. 2ff, EHV). Compare with Moses’ words to Israel shortly before his death: “Remember what the Amalekites, without any fear of God, did to you on your journey after you came out of Egypt. Remember how they confronted you on the way, when you were weak and tired, and they cut off all the stragglers among you, the ones who were lagging behind” (Dt 25:17,18, EHV). “So Saul summoned the troops and organized them in Telaim (טְּלָאִ֔ים): 200,000 footsoldiers, as well as 10,000 men from Judah” (1 Samuel 15:4, SE). Telaim is probably identical with Telem (טֶ֖לֶם), which was among the cities listed in Joshua 15:21ff, “at the southern edge of the tribe of the people of Judah along the border with Edom” (EHV, Telem listed in verse 24). It was fitting to organize the assembled people there before continuing to march directly south toward the northern point of the Gulf of Aqaba and against the Amalekites. “And Saul defeated the Amalekites from Havilah as far as Shur, which is east of Egypt” (1 Sam 15:7, ESV), that is, the northern part of the Gulf of Aqaba.

That “the wilderness of Shur is east of the Gulf of Suez and in the western area of the Sinai” is not at all proven by Genesis 16:7 and 1 Samuel 15:7. According to Exodus 15:22, the Israelites came to “the wilderness of Shur” about 20 days after the start of the exodus, after an all-night march across the Gulf of Aqaba (Yam-Suf) where, through a miracle of God, the waters piled up and the waves rose like a wall around them (Ex 15:8).

The Amalekites, as well as the Midianites, pressed in on and harassed Israel several times, both in the wilderness of the Negev and north east of the Dead Sea. The Midianites worked together with Moab several times (see Nu 22-24 and Judges 3:12ff). Later, “Midian and Amalek and the people of the East would go up against Israel. They would set up camp against them and ruin the crops all the way to Gaza” (Judges 6:3-4, EHV) before Gideon became the judge and savior of the land (see Judges 6-8).

Later, when the Ammonites attacked Israel, Jephthah became judge and savior. He sent messengers to the king of the Ammonites to say: “Israel did not take the land of Moab or the land of Ammon. Instead, when they came up from Egypt, Israel traveled through the wilderness as far as Yam-Suf (Hebr. עַד־יַם־ס֔וּף–NOTE: this means that they did not come to Yam-Suf already at the start of the exodus), and they came to Kadesh (at the end of the 40 years). Israel then sent messengers to the king of Edom, saying, ‘Please, let me cross over your land,’ but the king of Edom would not listen (see Numbers 20:14ff). In the same way Israel sent messengers to the king of Moab, but the king of Moab also was not willing, so Israel returned to Kadesh” (Judges 11:15-17, EHV alt.). Note also what the Israelites said when they had turned off the wilderness road and had become completely trapped before Yam-Suf: They said to Moses, “Is it because there are no graves in Egypt that you have taken us away to die in the wilderness? What have you done to us in bringing us out of Egypt? Is not this what we said to you in Egypt: ‘Leave us alone that we may serve the Egyptians’? For it would have been better for us to serve the Egyptians than to die in the wilderness” (Ex 14:11-12, ESV).

[1] Originally published as Från träldom till det utlovade landet in Biblicum Volume 84 Number 3, 2020. Biblicum, Hantverkaregatan 8 B, SE-341 Ljungby, www.biblicum.se . Translated to English by Julius Buelow.

[2] Brown, F., Driver, S. R., & Briggs, C. A. (1977). Enhanced Brown-Driver-Briggs Hebrew and English Lexicon (p. 410). Oxford: Clarendon Press.

[3] Brown, F., Driver, S. R., & Briggs, C. A. (1977). Enhanced Brown-Driver-Briggs Hebrew and English Lexicon (pp. 692–693). Oxford: Clarendon Press. “סוּף vb. come to an end, cease…”

[4] Brown, F., Driver, S. R., & Briggs, C. A. (1977). Enhanced Brown-Driver-Briggs Hebrew and English Lexicon (p. 693). Oxford: Clarendon Press.

[5] Brown, F., Driver, S. R., & Briggs, C. A. (1977). Enhanced Brown-Driver-Briggs Hebrew and English Lexicon (p. 1004). Oxford: Clarendon Press.

[6] Genesis 25:18 says this about Ishmael’s descendants: They “lived between Havilah and Shur, east of Egypt, as you go toward Assyria.” Havilah means “land of sand” and refers to the Arabian wilderness, “east of Egypt.” “The road to Assyria” was called “The King’s Road” and was a known caravan route which went from Egypt and then turned directly north at the northern point of the Gulf of Aqaba, east of the Dead Sea and the Jordan River.

[7] Still today the boundary between the land of Canaan (Israel) and Egypt goes from the Gulf of Aqaba to the northwest and along Egypt’s brook (= Wadi el-Arish), which empties into the Mediterranean Sea just south of Gaza. In Exodus 23:31 this border is referred to with the words “from Yam-Suf to the Sea of the Philistines.”

[8] Brown, F., Driver, S. R., & Briggs, C. A. (1977). Enhanced Brown-Driver-Briggs Hebrew and English Lexicon (p. 359). Oxford: Clarendon Press. III. חרר

[9] Another example of an old tradition that is permitted to force an interpretation of a biblical text is the interpretation of the wise men’s visit to the Christ child. According to ancient tradition, illustrated by many popular manger scenes, the wise men came to the manger fairly soon after Jesus’ birth and watched over him in the place where he was laid in manger. If one lets the testimony of the Bible speak, it becomes clear that the wise men’s visit could have happened 41 days after Jesus’ birth at the very earliest, that is, after the holy family had come back from the purification in Jerusalem (Luke 2:22) and no longer lived in a stall. For immediately after the wise men’s visit, the holy family fled to Egypt. Therefore the holy family’s trip to Jerusalem on the 40th day must have taken place before the wise men came. See the article “Förmånen att ha tillgång till hela Bibeln,” Biblicum nr 2/2020, p. 50ff.